Why would you want to do that?

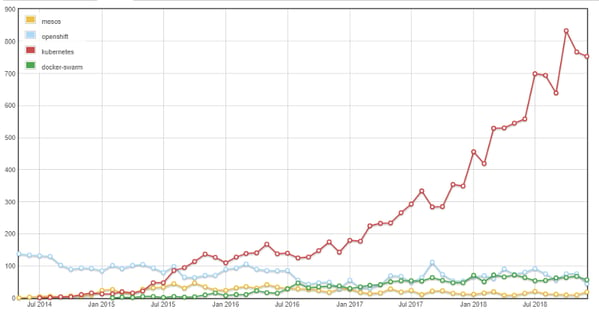

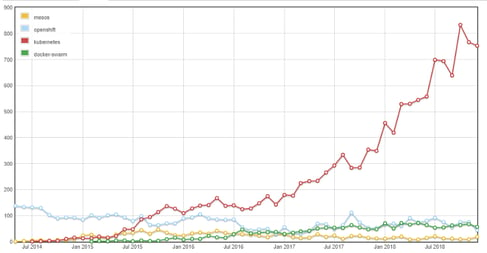

Nearly every day I hear about someone looking to move more workloads onto Kubernetes. This makes sense as the below data from StackOverflow indicatesthat Kubernetes usage has skyrocketed.

This differs from 2017, when I was mostly asked about how running Kubernetes via OpenShift, Rancher, Kubespray, or from the source compares to buying it by the drip from the Big 3. Now at MayaData and in the OpenEBS community we are often asked for advice about running your own Redis or Cassandra or MongoDB. The comparison these users are making is the DB as a service offerings from the Big 3, or even from the DB providers themselves.

So, the first question we need to ask is why? Why would you want to take on the responsibility of doing this yourself? Without digressing too far, I’ll simply summarize the answer this way: “For the same reason we run Kubernetes.” Broadly speaking, users want to run Kubernetes either to go faster or to save money — or both. They want to do so while minimizing headaches and risks. Users want everything to be Kubernetes native and to simply work.

Of course, when it comes to data, security is a top priority as well. Many enterprises such as financial service and health care providers, or those concerned about AWS as a competitor choose to run Kubernetes on their own environments. This is in part due to concerns about sensitive data being viewed by the cloud provider or by a malicious attacker. And yes, we have seen many OpenEBS users use local encryption, which seems to validate that trend.

DBaaS Alternatives

With each of the major cloud offerings, you can buy many flavors of DBaaS. Your choice will likely depend on your technical requirements and, of course, on your relationship with these cloud vendors. Generally speaking, you will want a high-quality solution that minimizes downtime and delivers exactly what your engineers need with minimum hassle.

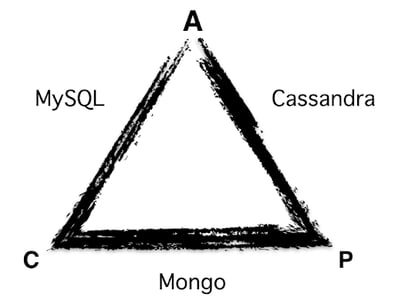

A common way to analyze the variety of DBs is to examine the CAP theorem and what your applications need. Typically, the rule of thumb is you pick two out of three. There are many, many blogs and discussions on picking a DB , but the idea is that there are an ever growing number of DBs, and a subset of those are run as a service by tier one clouds.

A quick aside on data base flavors:

There are many available DB solutions, many of which have little in common other than their primary task of ordering data for faster storage or access for a particular use case. There are at least eight main types:

- Key value stores — such as the ETCD inside of Kubernetes

- Column stores — such as Amazon’s Redshift. These are generally most efficient for analytics. SAP Hana is a famous proprietary in memory DB often classified as a columnar DB

- Document stores — such as MongoDB

- Graph databases — such as Neo4J

- Row stores — Although sometimes referred to as a columnar store, Cassandra actually belongs to this category. Generally, row oriented DBs are better at writes.

- In memory databases — such as Redis (please note our VP of Product is speaking at the April 2–3 Redis conf on considerations on Kubernetes)

- “Synthetic”—such as CockroachDB, NuoDB and TiDB. These are able to retain consistency while scaling horizontally reads and writes, so arguably stretching or even making moot the ACP trade off highlighted above

- Time series databases such as Influx DB, which often runs under Prometheus, arguably the most common stateful workload on Kubernetes. This is the default monitoring solution; you can read more about using OpenEBS under Prometheus in this blog post from October 2018: https://blog.openebs.io/using-openebs-as-the-tsdb-for-prometheus-fac3744d5507.

Relatively old and well-known SQL solutions seem to be extremely prevalent for a variety of reasons , such as the decreasing sizes of some workloads as microservices take off. Architectures increasingly use message systems like Kafka along with service meshes to pass relevant information and data back and forth, as opposed to dropping everything into shared NoSQL platforms. This is likely one reason that we see an enormous amount of PostgreSQL and MySQL applications running on top of OpenEBS. There are some distributed SQL systems that scale out and yet retain SQL semantics. Notable examples include TiDB and Couchase, each of which have key value stores ordering underlying data structures, and NuoDB, which is based upon a distributed memory cache. In between are solutions such as Vitess that take MySQL (or similar) and manage sharding and some of the operational automation needed to scale MySQL horizontally.

You can get a subset of these varieties from the cloud ventures as services. So, why are users increasingly running their own DBaaS? In addition to the obvious points above, more control, including running the particular DB du jour, and less spending and fewer security concerns. Whether they are well founded or not,why else might users select to build and operate their own DBaaS?

Compose a Stack that Better Serves the DB

DBs are themselves composed of pieces of software that have different requirements. You also have choices as to which underlying storage engines you use with each database and how you configure these storage engines as well. As an example, depending on the version and underlying storage engine being utilized, MongoDB has a journal, various data directories, and a replication log. Cassandra has commit_logs, data_files, and saved_caches. Similarly, PostgreSQL has a WAL director and data directory. With today’s container attached storage systems and the storage class construct in Kubernetes, you can easily match each component of a DB to a well-suited and tuned underlying storage component.

As an aside, if you’d like to learn about the differences between BTrees and LSM approaches, their underlying storage engines, and related concepts tying back to the underlying computer science, you would benefit from this talk given by Damian Gryski last year:

So, while the permutations of DBs are nearly endless, with many examples of many types of DBs that can be configured differently, you can use all of them on a common storage layer across any underlying physical disk or cloud volume. This can be done with the help of a solution like OpenEBS that is typically automatically customized for each permutation.

You can read more about storage for each component of a DB in the documentation of the many flavors of DBs; for example, the MongoDB documentation states:

It is probably worth also noting that to deal with disk or SSD failures, the MongoDB documentation also suggests the use of RAID 10.

Easily Integrate your Disparate Data Sources

We have seen that DBs increasingly do only one thing, and do it very well. This microservices approach to DBs relies on systems like Kafka to perform cross DB and other data source integration and streaming. This is opposed to having one external storage system provide integration of all the data with all of the attendant blast radius and difficulties that could entail. Now much of the data may end up in Snowflake or some on premise equivalent after an ETL process, of course. Ironically, integrating all of these data sources can sometimes be easier if these DBs are known to do one thing very well within your environment.

DevOps Autonomy

One fundamental precept of DevOps is to have small teams pick their own tools. Having each team choose their own DB solution fits this pattern, whereas having one mega DBaaS solution often does not.

What’s the catch? Operations.

Here at MayaData, we are huge believers in the power of Kubernetes as a foundation for more automated operations. However, we also see quite a bit of churn or diversity in approaches to building and running stateful workloads.

Currently, it seems like every flavor of DB and stateful workload is coming out with at least one Kubernetes operator. And while that is great, it is also somewhat concerning. Having co-founded the leader in event driven automation, StackStorm, I’ve spent many years dealing with this day two operations stuff and, well, it is hard. In my opinion, we need to embrace workflow for some of this work, whether it is Argo that is now integrated into Kubeflow or StackStorm. This sports a new container friendly and extremely powerful workflow engine called Orquesta at its core. Incidentally, Orquesta can be easily embedded into other projects, and I expect and hope to see this happening more as we continue in 2019. By workflow, I mean using an engine that makes explicit the common process events such as forks, joins, conditional pauses, for example, and does so in a way that allows humans to better grok and share these patterns.

Along these lines, back in October of 2015 I helped author a blog about how Netflix and others use StackStorm for Cassandra operations.

https://stackstorm.com/2015/10/02/tutorial-of-the-week-cassandra-auto-remediation/

If you are interested in workflows for operations, by the way, you might find interesting this overview of the space by my StackStorm co-founder Dmitri Zimine, which also discusses the offerings from the Big 3 cloud vendors, who are positioning their workflow engines as glue to tie together functions from their serverless offerings: https://thenewstack.io/serverless-and-workflows-the-present-and-the-future/

So — where does storage fit into all of this?

Whether or not you choose to use a generalizable approach to operators or use one of the many one-offs emerging in the Kubernetes community, you can approach a level of generalization through the use of Container Attached Storage. While storage and related capabilities will not completely care for your stateful workloads, it can provide some common services that every database needs, and thereby allow engineers to focus on those particular aspects of each DB that need their attention.

I’ve assembled common requirements into a table, as we often get questions from the community (and investors, customers, and new team members) that suggest that the lines between the dozens of DBs fighting for attention and underlying containerized storage sometimes seems lost in all the hubbub. For example, did you know that storage engines for DBs are not “really storage”? Feel free to make comments below or even better, ask questions on StackOverflow or on our Slack community: https://slack.openebs.io.

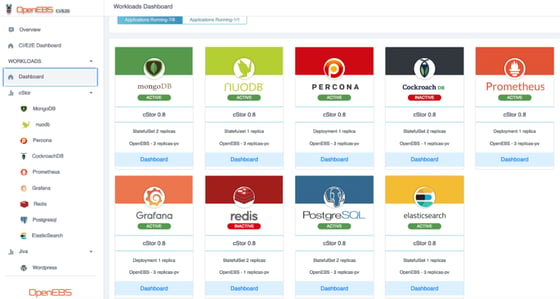

We’ve recently completed the testing and creation of some recommended storage classes with one of the largest NoSQL community projects. You can always see each commit to Master of OpenEBS being tested against a variety of common data based on OpenEBS.ci as well. Grab both the storage classes and the configuration for the systems doing this testing as well if you are interested.

Conclusion

This blog was intended to outline some things to think about when running your own DBaaS. While I recommend considering these, I also suggest that you should think long and hard about operations automation and, of course, underlying data resilience.

At MayaData, we are actively working on a number of DBaaS implementations for enterprises and are happy to share best practices via discussions on Slack and elsewhere. Please do get in touch. Together, we are enabling tremendous boosts in data agility, often with the help of DBaaS deployments. Whatever your permutation of DB or other stateful workload, we are here to do our part in helping you to achieve true data agility.

This article was first published on Feb 14, 2018 on OpenEBS's Medium Account.

Game changer in Container and Storage Paradigm- MayaData gets acquired by DataCore Software

Don Williams

Don Williams

Managing Ephemeral Storage on Kubernetes with OpenEBS

Kiran Mova

Kiran Mova

Understanding Persistent Volumes and PVCs in Kubernetes & OpenEBS

Murat Karslioglu

Murat Karslioglu